Benedict Arnold was once a patriotic war hero valued by George Washington and admired by his men. But now his name is synonymous with traitor. What could have led Arnold to ruin his legacy by betraying his fellow Americans during the Revolutionary War?

Analysis of Arnold’s actions have been simplified over the years to serve a narrative of right and wrong. While Arnold’s betrayal was clear—he offered the British seizure of the military fortress at West Point, NY, in exchange for 10,000 pounds and a British military commission—what led up to that moment of betrayal is more complicated and less political than is often taught.

Analysis of Arnold’s actions have been simplified over the years to serve a narrative of right and wrong. While Arnold’s betrayal was clear—he offered the British seizure of the military fortress at West Point, NY, in exchange for 10,000 pounds and a British military commission—what led up to that moment of betrayal is more complicated and less political than is often taught.

Arnold was the victim of a smear campaign.

Some would say the catalyst was Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council President Joseph Reed.

He took a personal dislike to Arnold and, in 1779, attempted to prosecute him on a series of treason charges ranging from buying illegal goods to preferring the company of British loyalists. In the build-up of his case, Reed was known to spread rumors about Arnold without offering proof of his allegations.

Arnold’s wife encouraged his treason.

Arnold was also deeply in debt and newly married to an ambitious woman. His wife, Peggy, was the daughter of a prominent Philadelphia family with loyalist leanings that had fared better under the British.

Peggy was accustomed to a certain level of living and some historians believe that Peggy steered Arnold to the British in order to maintain that lifestyle. Becoming a traitor to his country could fetch him a handsome payment from the British.

Letters suggest Arnold had character issues.

But there were plenty of other reasons, too. Eric D. Lehman, author of Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New London, notes that others at the time had similar circumstances and did not betray their country. Lehman spent time looking over Arnold’s letters and other first-hand accounts.

“Some seemed to point to him ‘lacking feeling,’ i.e. sociopathic, but others showed him having too much feeling—he couldn’t control his temper. The number one thing I found across all of them was his selfish ambition, which came from a profound lack of self-esteem as a child and young man,” Lehman says.

Benedict Arnold, seated at the table, as he hands papers to British officer John Andre during the American Revolutionary War. (Credit: Stock Montage/Getty Images)

Traditionally Arnold’s story has been taught with a good-versus-evil simplicity. More recently, Lehman points out, the tendency has been to portray Arnold as a misunderstood heroic figure.

“Both simplifications are a mistake in my view,” says Lehman. “He was certainly misunderstood, and he was a hero in the early years of the war. That should always be part of the story.

“But he also betrayed his close friends, was willing to allow the death of and actually kill former comrades, and earned the name ‘traitor’ from both friend and foe. If we leave that out, we simplify the story by omission. If we can’t hold those two ideas in our head at the same time, we are in good company. People like [Marquis de] Lafayette and [George] Washington couldn’t either.”

Even the British disparaged Arnold for his turncoat ways.

Lehman thinks it’s important to remember the whole story of Arnold—his betrayal wasn’t just treason. The British, who had much to gain from Arnold switching sides, found him dishonorable and untrustworthy.

“One thing that has been left out of so many tellings of Arnold’s story is that he didn’t stop after his West Point treason was discovered,” Lehman points out. “He went on to attack Virginia—almost capturing Thomas Jefferson—and then attacking Connecticut, his home state.

“Spying was one thing, but his willingness to switch sides in the middle of an armed conflict, and fight against the men who had a year earlier been fighting by his side, was something that people of that time and maybe ours could simply not understand.”

Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) was an early American hero of the Revolutionary War (1775-83) who later became one of the most infamous traitors in U.S. history after he switched sides and fought for the British. At the outbreak of the war, Arnold participated in the capture of the British garrison of Fort Ticonderoga in 1775. In 1776, he hindered a British invasion of New York at the Battle of Lake Champlain. The following year, he played a crucial role in bringing about the surrender of British General John Burgoyne’s (1722-92) army at Saratoga. Yet Arnold never received the recognition he thought he deserved. In 1779, he entered into secret negotiations with the British, agreeing to turn over the U.S. post at West Point in return for money and a command in the British army. The plot was discovered, but Arnold escaped to British lines. His name has since become synonymous with the word “traitor.”

EARLY LIFE

Benedict Arnold was born on January 14, 1741, in Norwich, Connecticut. His mother came from a wealthy family, but his father squandered their estate. As a young man, Arnold apprenticed at an apothecary business and served in the militia during the French and Indian War (1754-63).

In 1767, Arnold, who became a prosperous trader, married Margaret Mansfield. The couple had three children before Margaret’s death in 1775.

HERO OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

When the Revolutionary War broke out between Great Britain and its 13 American colonies in April 1775, Arnold joined the Continental Army. Acting under a commission from the revolutionary government of Massachusetts, Arnold partnered with Vermont frontiersman Ethan Allen (1738-89) and Allen’s Green Mountain Boys to capture the unsuspecting British garrison at Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York on May 10, 1775. Later that year, Arnold led an ill-fated expedition on a harrowing trek from Maine to Quebec. The purpose of the expedition was to rally the inhabitants of Canada behind the Patriot cause and deprive the British government of a northern base from which to mount strikes into the 13 colonies. With the enlistments of many of his men expiring on New Year’s Day, Arnold had no choice but to launch a desperate attack against well-fortified Quebec City through a blizzard on December 31, 1775. Early in the battle, Arnold received a grave wound to his leg and was carried to the back of the battlefield. The assault continued, but failed miserably. Hundreds of American soldiers were killed, wounded or captured, and Canada remained in British hands.

By the later part of 1776, Arnold had recovered sufficiently from his wound to once again take the field. He played a crucial role in hindering a British invasion from Canada into New York in the autumn of that year. Correctly predicting that British General Guy Carleton (1724-1808) would sail an invading force down Lake Champlain, Arnold supervised the hasty construction of an American flotilla on that lake to meet Carleton’s fleet. On October 11, 1776, the American fleet surprised its foe near Valcour Bay. Although Carleton’s flotilla drove the Americans away, Arnold’s action delayed Carleton’s approach long enough that, by the time the British general reached New York, the battle season was near an end, and the British had to return to Canada. Arnold’s performance at the Battle of Lake Champlain rescued the Patriot cause from potential disaster.

Despite his heroic service, Arnold felt he did not receive the recognition he deserved. He resigned from the Continental Army in 1777 after Congress promoted five junior officers above him. General George Washington (1732-99), the commander in chief of the Continental Army, urged Arnold to reconsider. Arnold rejoined the army in time to participate in the defense of central New York from an invading British force under General John Burgoyne in the fall of 1777.

In the battles against Burgoyne, Arnold served under General Horatio Gates (1728-1806), an officer whom Arnold came to hold in contempt. The antipathy was mutual, and Gates at one point relieved Arnold of his command. Nonetheless, at the pivotal Battle of Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777, Arnold defied Gates’ authority and took command of a group of American soldiers whom he led in an assault against the British line. Arnold’s attack threw the enemy into disarray and contributed greatly to the American victory. Ten days later, Burgoyne surrendered his entire army at Saratoga. News of the surrender convinced France to enter the war on the side of the Americans. Once again, Arnold had brought his country a step closer to independence. However, Gates downplayed Arnold’s contributions in his official reports and claimed most of the credit for himself.

Meanwhile, Arnold seriously wounded the same leg he had injured at Quebec in the battle. Rendered temporarily incapable of a field command, he accepted the position of military governor of Philadelphia in 1778. While there, his loyalties began to change.

A TREACHEROUS PLOT

During his term as governor, rumors, not entirely unfounded, circulated through Philadelphia accusing Arnold of abusing his position for his personal profit. Questions were also raised about Arnold’s courtship and marriage to the young Peggy Shippen (1760-1804), the daughter of a man suspected of Loyalist sympathies. Arnold and his second wife, with whom he would have five children, lived a lavish lifestyle in Philadelphia, accumulating substantial debt. The debt and the resentment Arnold felt over not being promoted faster were motivating factors in his choice to become a turncoat. He concluded that his interests would be better served assisting the British than continuing to suffer for an American army he saw as ungrateful.

By the end of 1779, Arnold had begun secret negotiations with the British to surrender the American fort at West Point, New York, in return for money and a command in the British army. Arnold’s chief intermediary was British Major John André (1750-80). André was captured in September 1780, while crossing between British and American lines, disguised in civilian clothes. Papers found on André incriminated Arnold in treason. Learning of André’s capture, Arnold fled to British lines before the Patriots could arrest him. West Point remained in American hands, and Arnold only received a portion of his promised bounty. André was hanged as a spy in October 1780.

Arnold soon became one of the most reviled figures in U.S. history. Ironically, his treason became his final service to the American cause. By 1780, Americans had grown frustrated with the slow progress toward independence and their numerous battlefield defeats. However, word of Arnold’s treachery re-energized the Patriots’ sagging morale.

LATER LIFE

After fleeing to the enemy side, Arnold received a commission with the British army and served in several minor engagements against the Americans. After the war, which ended in victory for the Americans with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Arnold resided in England. He died in London on June 14, 1801, at age 60. The British regarded him with ambivalence, while his former countrymen despised him. Following his death, Arnold’s memory lived on in the land of his birth, where his name became synonymous with the word “traitor.”

Before Benedict Arnold Became an Infamous Traitor, He Tried to Invade Canada

Benedict Arnold is now known mostly as a notorious Revolutionary War traitor who secretly tried to sell out the fort at West Point in exchange for a payoff and a commission in the British Army. But except for a few unfortunate twists of fate, Arnold instead might have gone down in history as one of the war’s great heroes. His audacious plan to lead a 1775 expedition through the wilderness to capture Quebec City was seen as a visionary strategy to prompt the province of Quebec to join the rebellion against the British.

But it didn’t work out that way.

Arnold’s expedition turned into a disastrous defeat, one that nearly cost him his own life and helped stunt his career as an American officer. The botched mission started him on the road to disillusionment and treason. But Arnold’s plan itself actually wasn’t that bad of an idea.

Arnold convinced George Washington they needed Canada on their side.

“The strategy itself was brilliant,” explains Willard Sterne Randall, a professor emeritus of history at Champlain College and author of the 1990 biography Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor, as well as numerous other works on early American history. “Benedict Arnold was a brilliant strategist, but in this case, a terrible tactician.”

Arnold, who before the war had traded with Canadians and still had contacts there, first approached George Washington in the Spring of 1775 to propose an invasion of Canada, according to Joyce Lee Malcolm’s book The Tragedy of Benedict Arnold. Arnold argued that seizing Quebec had huge potential benefits. In addition to depriving the British of a potential staging area for attacking the 13 colonies from the north, Americans envisioned that French Canadians might seize the opportunity to rise up against the British and join in the fight for independence.

Washington probably didn’t need that much convincing, because from the American viewpoint, Canada seemed ripe for the picking. The British only had 775 troops in the entire country, according to Randall, and the then-capital of Quebec City was guarded by fewer than 300 soldiers.

Read more: Why Did Benedict Arnold Betray America?

In his letter to the Continental Congress, Arnold envisioned a straightforward march to Montreal. But as detailed in Thomas A. Desjardin’s book Through a Howling Wilderness, Washington opted instead to go with a complicated, two-pronged attack. One part of the force would head up through New York toward Montreal, while to the east, a second 1,050-man contingent led by Arnold would make their way through the Maine wilderness to Quebec City, with the aim of catching the British by surprise.

The expedition to Quebec was grueling.

It might have worked, except that as Randall notes, “everything went wrong.” Because of a holdup in getting pay for the men, the expedition got off to a late start in September. The map obtained by Arnold was inaccurate, and the route turned out to be far longer and more arduous than he had envisioned.

Worse yet, Randall says, the Maine shipbuilder hired by the expedition secretly was a British loyalist, and he deliberately used heavy green wood and left out the caulking, so that the barges laden with supplies soon sank in the Kennebec River. After a brutal hurricane wiped out more of their provisions and equipment, many of Arnold’s men deserted and headed back home. By the time Arnold finally got to his destination in November, he had only 675 starving, poorly armed soldiers left, according to Malcolm’s account.

Meanwhile, Sir Guy Carleton, the skillful, savvy British commander in Canada, had rushed to Quebec City. By the time Arnold got there, British reinforcements—battle-hardened Scottish veterans of the French and Indian War—had arrived to bolster the defenses.

“If Arnold had gotten to Quebec three days earlier, it might have worked,” Randall explains. “He almost pulled it off.”

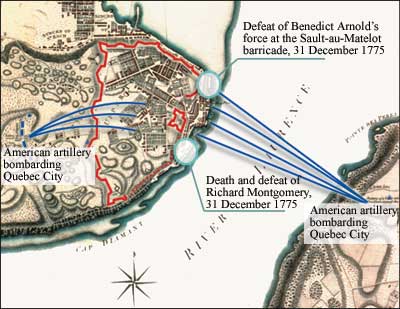

The city of Quebec and the Saint Laurence River at the time of the attack by United States Forces, circa 1775.

A New Year’s Eve attack in a blizzard fizzled.

Instead, after threatening to inflict “every severity” upon Quebec unless it surrendered, Arnold had to sit and wait for additional troops led by Maj. Gen. Richard Montgomery to arrive. As this 1990 article by Randall details, the Americans finally launched their assault on Quebec City on New Year’s Eve in a blinding blizzard, and it quickly turned into a disaster.

A single volley of cannon fire killed Montgomery and most of his officers, and Arnold was severely wounded in the leg by a rifle shot and had to be dragged off the field. (Here is Carleton’s account of the battle.) Most of the American force was killed, wounded or captured, so that of the 300 men who’d survived the journey with Arnold to Quebec, only 100 were left.

The brutal defeat “struck an amazing panick” among the Americans, as Arnold conceded in a dispatch to Washington a few weeks later. But to Arnold’s credit, he didn’t give up. Along with the tattered remainder of his forces, he cleverly kept up the siege, moving a single cannon around and firing at the fort to create the illusion that he had more artillery, according to Randall. In that fashion, Arnold held out until spring, when reinforcements from New England arrived, and he was ordered to return home.

“Arnold was superseded and pushed aside,” Randall says. It was the start of a pattern, in which his field experience and bravery was disregarded and he was repeatedly passed over in favor of other officers. “This was the beginning of his dilemma about which side to be on.”

Eventually, the arrival of a British fleet carrying 10,000 British regulars and German mercenaries in May 1776 forced the Americans to retreat for good.

The Quebec Act sealed French Canadians’ allegiance to the British.

The French Canadian uprising that Arnold and others had hoped for never materialized, thanks to the property and religious rights that the British had conferred in the Quebec Act of 1774. “The French Canadians were Catholics, and they’d just been given legal status by the British,” Randall explains. “They saw the American invasion as a Protestant invasion.”

Despite his failure to take Quebec, Arnold eventually did manage to prevent the British from attacking from the north. In October 1776, he hastily put together a small fleet of ships that met Carleton’s invading force in the Battle of Valcour Island, and put up such fierce resistance that the British had to turn back. Four years later, Arnold would switch sides—and cement his legacy as one of the most infamous traitors in history.