Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States from 1829 to 1837, seeking to act as the direct representative of the common man.

More nearly than any of his predecessors, Andrew Jackson was elected by popular vote; as President he sought to act as the direct representative of the common man.

Born in a backwoods settlement in the Carolinas in 1767, he received sporadic education. But in his late teens he read law for about two years, and he became an outstanding young lawyer in Tennessee. Fiercely jealous of his honor, he engaged in brawls, and in a duel killed a man who cast an unjustified slur on his wife Rachel.

Jackson prospered sufficiently to buy slaves and to build a mansion, the Hermitage, near Nashville. He was the first man elected from Tennessee to the House of Representatives, and he served briefly in the Senate. A major general in the War of 1812, Jackson became a national hero when he defeated the British at New Orleans.

In 1824 some state political factions rallied around Jackson; by 1828 enough had joined “Old Hickory” to win numerous state elections and control of the Federal administration in Washington.

In his first Annual Message to Congress, Jackson recommended eliminating the Electoral College. He also tried to democratize Federal officeholding. Already state machines were being built on patronage, and a New York Senator openly proclaimed “that to the victors belong the spoils. . . . ”

Jackson took a milder view. Decrying officeholders who seemed to enjoy life tenure, he believed Government duties could be “so plain and simple” that offices should rotate among deserving applicants.

As national politics polarized around Jackson and his opposition, two parties grew out of the old Republican Party–the Democratic Republicans, or Democrats, adhering to Jackson; and the National Republicans, or Whigs, opposing him.

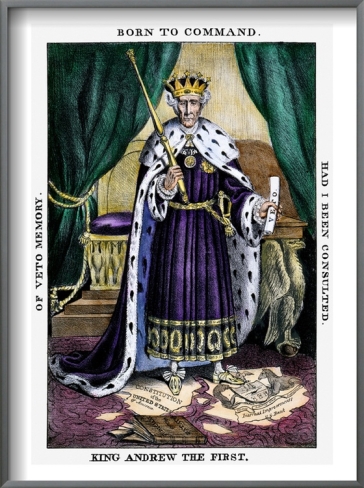

Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and other Whig leaders proclaimed themselves defenders of popular liberties against the usurpation of Jackson. Hostile cartoonists portrayed him as King Andrew I.

Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and other Whig leaders proclaimed themselves defenders of popular liberties against the usurpation of Jackson. Hostile cartoonists portrayed him as King Andrew I.

Behind their accusations lay the fact that Jackson, unlike previous Presidents, did not defer to Congress in policy-making but used his power of the veto and his party leadership to assume command.

The greatest party battle centered around the Second Bank of the United States, a private corporation but virtually a Government-sponsored monopoly. When Jackson appeared hostile toward it, the Bank threw its power against him.

Clay and Webster, who had acted as attorneys for the Bank, led the fight for its recharter in Congress. “The bank,” Jackson told Martin Van Buren, “is trying to kill me, but I will kill it!” Jackson, in vetoing the recharter bill, charged the Bank with undue economic privilege.

His views won approval from the American electorate; in 1832 he polled more than 56 percent of the popular vote and almost five times as many electoral votes as Clay.

Jackson met head-on the challenge of John C. Calhoun, leader of forces trying to rid themselves of a high protective tariff.

When South Carolina undertook to nullify the tariff, Jackson ordered armed forces to Charleston and privately threatened to hang Calhoun. Violence seemed imminent until Clay negotiated a compromise: tariffs were lowered and South Carolina dropped nullification.

In January of 1832, while the President was dining with friends at the White House, someone whispered to him that the Senate had rejected the nomination of Martin Van Buren as Minister to England. Jackson jumped to his feet and exclaimed, “By the Eternal! I’ll smash them!” So he did. His favorite, Van Buren, became Vice President, and succeeded to the Presidency when “Old Hickory” retired to the Hermitage, where he died in June 1845.

The definitive biography of a larger-than-life president who defied norms, divided a nation, and changed Washington forever

Andrew Jackson, his intimate circle of friends, and his tumultuous times are at the heart of this remarkable book about the man who rose from nothing to create the modern presidency. Beloved and hated, venerated and reviled, Andrew Jackson was an orphan who fought his way to the pinnacle of power, bending the nation to his will in the cause of democracy. Jackson’s election in 1828 ushered in a new and lasting era in which the people, not distant elites, were the guiding force in American politics. Democracy made its stand in the Jackson years, and he gave voice to the hopes and the fears of a restless, changing nation facing challenging times at home and threats abroad. To tell the saga of Jackson’s presidency, acclaimed author Jon Meacham goes inside the Jackson White House. Drawing on newly discovered family letters and papers, he details the human drama-the family, the women, and the inner circle of advisers- that shaped Jackson’s private world through years of storm and victory.

One of our most significant yet dimly recalled presidents, Jackson was a battle-hardened warrior, the founder of the Democratic Party, and the architect of the presidency as we know it. His story is one of violence, sex, courage, and tragedy. With his powerful persona, his evident bravery, and his mystical connection to the people, Jackson moved the White House from the periphery of government to the center of national action, articulating a vision of change that challenged entrenched interests to heed the popular will- or face his formidable wrath. The greatest of the presidents who have followed Jackson in the White House-from Lincoln to Theodore Roosevelt to FDR to Truman-have found inspiration in his example, and virtue in his vision.

Jackson was the most contradictory of men. The architect of the removal of Indians from their native lands, he was warmly sentimental and risked everything to give more power to ordinary citizens. He was, in short, a lot like his country: alternately kind and vicious, brilliant and blind; and a man who fought a lifelong war to keep the republic safe-no matter what it took.

Born in poverty, Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) had become a wealthy Tennessee lawyer and rising young politician by 1812, when war broke out between the United States and Britain. His leadership in that conflict earned Jackson national fame as a military hero, and he would become America’s most influential–and polarizing–political figure during the 1820s and 1830s. After narrowly losing to John Quincy Adams in the contentious 1824 presidential election, Jackson returned four years later to win redemption, soundly defeating Adams and becoming the nation’s seventh president (1829-1837). As America’s political party system developed, Jackson became the leader of the new Democratic Party. A supporter of states’ rights and slavery’s extension into the new western territories, he opposed the Whig Party and Congress on polarizing issues such as the Bank of the United States. For some, his legacy is tarnished by his role in the forced relocation of Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi.

ANDREW JACKSON’S EARLY LIFE

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, in the Waxhaws region on the border of North and South Carolina. The exact location of his birth is uncertain, and both states have claimed him as a native son; Jackson himself maintained he was from South Carolina. The son of Irish immigrants, Jackson received little formal schooling. The British invaded the Carolinas in 1780-1781, and Jackson’s mother and two brothers died during the conflict, leaving him with a lifelong hostility toward Great Britain.

Jackson read law in his late teens and earned admission to the North Carolinabar in 1787. He soon moved west of the Appalachians to the region that would soon become the state of Tennessee, and began working as a prosecuting attorney in the settlement that became Nashville. He later set up his own private practice and met and married Rachel (Donelson) Robards, the daughter of a local colonel. Jackson grew prosperous enough to build a mansion, the Hermitage, near Nashville, and to buy slaves. In 1796, Jackson joined a convention charged with drafting the new Tennessee state constitution and became the first man to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee. Though he declined to seek reelection and returned home in March 1797, he was almost immediately elected to the U.S. Senate. Jackson resigned a year later and was elected judge of Tennessee’s superior court. He was later chosen to head the state militia, a position he held when war broke out with Great Britain in 1812.

ANDREW JACKSON’S MILITARY CAREER

Andrew Jackson, who served as a major general in the War of 1812, commanded U.S. forces in a five-month campaign against the Creek Indians, allies of the British. After that campaign ended in a decisive American victory in the Battle of Tohopeka (or Horseshoe Bend) in Alabama in mid-1814, Jackson led American forces to victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans (January 1815). The win, which occurred after the War of 1812 officially ended but before news of the Treaty of Ghent had reached Washington, elevated Jackson to the status of national war hero. In 1817, acting as commander of the army’s southern district, Jackson ordered an invasion of Florida. After his forces captured Spanish posts at St. Mark’s and Pensacola, he claimed the surrounding land for the United States. The Spanish government vehemently protested, and Jackson’s actions sparked a heated debate in Washington. Though many argued for Jackson’s censure, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams defended the general’s actions, and in the end they helped speed the American acquisition of Florida in 1821.

Jackson’s popularity led to suggestions that he run for president. At first he professed no interest in the office, but by 1824 his boosters had rallied enough support to get him a nomination as well as a seat in the U.S. Senate. In a five-way race, Jackson won the popular vote, but for the first time in history no candidate received a majority of electoral votes. The House of Representatives was charged with deciding between the three leading candidates: Jackson, Adams and Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford. Critically ill after a stroke, Crawford was essentially out, and Speaker of the House Henry Clay (who had finished fourth) threw his support behind Adams, who later made Clay his secretary of state. Jackson’s supporters raged against what they called the “corrupt bargain” between Clay and Adams, and Jackson himself resigned from the Senate.

ANDREW JACKSON IN THE WHITE HOUSE

Andrew Jackson won redemption four years later in an election that was characterized to an unusual degree by negative personal attacks. Jackson and his wife were accused of adultery on the basis that Rachel had not been legally divorced from her first husband when she married Jackson. Shortly after his victory in 1828, the shy and pious Rachel died at the Hermitage; Jackson apparently believed the negative attacks had hastened her death. The Jacksons did not have any children but were close to their nephews and nieces, and one niece, Emily Donelson, would serve as Jackson’s hostess in the White House.

Jackson was the nation’s first frontier president, and his election marked a turning point in American politics, as the center of political power shifted from East to West. “Old Hickory” was an undoubtedly strong personality, and his supporters and opponents would shape themselves into two emerging political parties: The pro-Jacksonites became the Democrats (formally Democrat-Republicans) and the anti-Jacksonites (led by Clay and Daniel Webster) were known as the Whig Party. Jackson made it clear that he was the absolute ruler of his administration’s policy, and he did not defer to Congress or hesitate to use his presidential veto power. For their part, the Whigs claimed to be defending popular liberties against the autocratic Jackson, who was referred to in negative cartoons as “King Andrew I.”

BANK OF THE UNITED STATES AND CRISIS IN SOUTH CAROLINA

A major battle between the two emerging political parties involved the Bank of the United States, the charter of which was due to expire in 1832. Andrew Jackson and his supporters opposed the bank, seeing it as a privileged institution and the enemy of the common people; meanwhile, Clay and Webster led the argument in Congress for its recharter. In July, Jackson vetoed the recharter, charging that the bank constituted the “prostration of our Government to the advancement of the few at the expense of the many.” Despite the controversial veto, Jackson won reelection easily over Clay, with more than 56 percent of the popular vote and five times more electoral votes.

Though in principle Jackson supported states’ rights, he confronted the issue head-on in his battle against the South Carolina legislature, led by the formidable Senator John C. Calhoun. In 1832, South Carolina adopted a resolution declaring federal tariffs passed in 1828 and 1832 null and void and prohibiting their enforcement within state boundaries. While urging Congress to lower the high tariffs, Jackson sought and obtained the authority to order federal armed forces to South Carolina to enforce federal laws. Violence seemed imminent, but South Carolina backed down, and Jackson earned credit for preserving the Union in its greatest moment of crisis to that date.

ANDREW JACKSON’S LEGACY

In contrast to his strong stand against South Carolina, Andrew Jackson took no action after Georgia claimed millions of acres of land that had been guaranteed to the Cherokee Indians under federal law, and he declined to enforce a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that Georgia had no authority over Native American tribal lands. In 1835, the Cherokees signed a treaty giving up their land in exchange for territory west of Arkansas, where in 1838 some 15,000 would head on foot along the so-called Trail of Tears. The relocation resulted in the deaths of thousands.

In the 1836 election, Jackson’s chosen successor Martin Van Buren defeated Whig candidate William Henry Harrison, and Old Hickory left the White House even more popular than when he had entered it. Jackson’s success seemed to have vindicated the still-new democratic experiment, and his supporters had built a well-organized Democratic Party that would become a formidable force in American politics. After leaving office, Jackson retired to the Hermitage, where he died in June 1845.