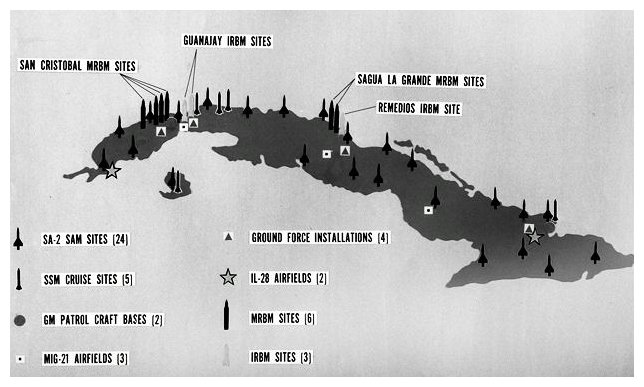

In a televised speech of extraordinary gravity, President John F. Kennedy announces that U.S. spy planes have discovered Soviet missile bases in Cuba. These missile sites—under construction but nearing completion—housed medium-range missiles capable of striking a number of major cities in the United States, including Washington, D.C. Kennedy announced that he was ordering a naval “quarantine” of Cuba to prevent Soviet ships from transporting any more offensive weapons to the island and explained that the United States would not tolerate the existence of the missile sites currently in place. The president made it clear that America would not stop short of military action to end what he called a “clandestine, reckless, and provocative threat to world peace.”

On October 23, the quarantine of Cuba began, but Kennedy decided to give Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev more time to consider the U.S. action by pulling the quarantine line back 500 miles. By October 24, Soviet ships en route to Cuba capable of carrying military cargoes appeared to have slowed down, altered, or reversed their course as they approached the quarantine, with the exception of one ship—the tanker Bucharest. At the request of more than 40 nonaligned nations, U.N. Secretary-General U Thant sent private appeals to Kennedy and Khrushchev, urging that their governments “refrain from any action that may aggravate the situation and bring with it the risk of war.” At the direction of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, U.S. military forces went to DEFCON 2, the highest military alert ever reached in the postwar era, as military commanders prepared for full-scale war with the Soviet Union.

On October 23, the quarantine of Cuba began, but Kennedy decided to give Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev more time to consider the U.S. action by pulling the quarantine line back 500 miles. By October 24, Soviet ships en route to Cuba capable of carrying military cargoes appeared to have slowed down, altered, or reversed their course as they approached the quarantine, with the exception of one ship—the tanker Bucharest. At the request of more than 40 nonaligned nations, U.N. Secretary-General U Thant sent private appeals to Kennedy and Khrushchev, urging that their governments “refrain from any action that may aggravate the situation and bring with it the risk of war.” At the direction of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, U.S. military forces went to DEFCON 2, the highest military alert ever reached in the postwar era, as military commanders prepared for full-scale war with the Soviet Union.

On October 25, the aircraft carrier USS Essex and the destroyer USS Gearingattempted to intercept the Soviet tanker Bucharest as it crossed over the U.S. quarantine of Cuba. The Soviet ship failed to cooperate, but the U.S. Navy restrained itself from forcibly seizing the ship, deeming it unlikely that the tanker was carrying offensive weapons. On October 26, Kennedy learned that work on the missile bases was proceeding without interruption, and ExCom considered authorizing a U.S. invasion of Cuba. The same day, the Soviets transmitted a proposal for ending the crisis: The missile bases would be removed in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba.

The next day, however, Khrushchev upped the ante by publicly calling for the dismantling of U.S. missile bases in Turkey under pressure from Soviet military commanders. While Kennedy and his crisis advisers debated this dangerous turn in negotiations, a U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba, and its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, was killed. To the dismay of the Pentagon, Kennedy forbid a military retaliation unless any more surveillance planes were fired upon over Cuba. To defuse the worsening crisis, Kennedy and his advisers agreed to dismantle the U.S. missile sites in Turkey but at a later date, in order to prevent the protest of Turkey, a key NATO member.

On October 28, Khrushchev announced his government’s intent to dismantle and remove all offensive Soviet weapons in Cuba. With the airing of the public message on Radio Moscow, the USSR confirmed its willingness to proceed with the solution secretly proposed by the Americans the day before. In the afternoon, Soviet technicians began dismantling the missile sites, and the world stepped back from the brink of nuclear war. The Cuban Missile Crisis was effectively over. In November, Kennedy called off the blockade, and by the end of the year all the offensive missiles had left Cuba. Soon after, the United States quietly removed its missiles from Turkey.

The Cuban Missile Crisis seemed at the time a clear victory for the United States, but Cuba emerged from the episode with a much greater sense of security.The removal of antiquated Jupiter missiles from Turkey had no detrimental effect on U.S. nuclear strategy, but the Cuban Missile Crisis convinced a humiliated USSR to commence a massive nuclear buildup. In the 1970s, the Soviet Union reached nuclear parity with the United States and built intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of striking any city in the United States.

A succession of U.S. administrations honored Kennedy’s pledge not to invade Cuba, and relations with the communist island nation situated just 80 miles from Florida remained a thorn in the side of U.S. foreign policy for more than 50 years. In 2015, officials from both nations announced the formal normalization of relations between the U.S and Cuba, which included the easing of travel restrictions and the opening of embassies and diplomatic missions in both countries.

10 Things You May Not Know About the Cuban Missile Crisis

1. The U-2 aerial photographs were analyzed inside a secret office above a used car dealership.

The critical photographs snapped by U-2 reconnaissance planes over Cuba were shipped for analysis to a top-secret CIA facility in a most unlikely location: a building above the Steuart Ford car dealership in a rundown section of Washington, D.C. While used car salesmen were wheeling and dealing downstairs on October 15, 1962, upstairs CIA analysts in the state-of-the-art National Photographic Interpretation Center were working around the clock to scour hundreds of grainy photographs for evidence of a Soviet ballistic missile site under construction.

2. The Soviets relied on checkered shirts and tight quarters to sneak thousands of troops into Cuba.

Beginning in the summer of 1962, the Soviets employed an elaborate ruse, code-named Operation Anadyr, to ship thousands of combat troops to Cuba. A few thousand soldiers donned checkered shirts to pose as civilian agricultural advisers. Many more were issued Arctic equipment to throw off the scent, sent aboard a fleet of 85 ships and then told to remain below the decks for the long voyage in order to go undetected. When the CIA estimated on October 20, 1962, that 6,000 to 8,000 Soviet troops were stationed in Cuba, the true number was more than 40,000.

3. To keep news of the crisis from leaking, a concocted cold was blamed for President Kennedy’s cancellation of public events.

To avoid arousing public concerns in the first days of the crisis, Kennedy attempted to maintain his official schedule, including a planned seven-state campaign swing in advance of midterm elections. On October 20, 1962, however, he abruptly flew back from Chicago to Washington. The president’s physician fabricated a story that Kennedy’s voice had been “husky” the night before and that he was suffering from a cold and a slight fever. While aides told the press that Kennedy would spend the rest of the day in bed, he instead engaged in five hours of meetings with advisers before deciding on instituting a naval blockade of Cuba. Vice President Lyndon Johnson also blamed a cold for cutting short a trip to Honolulu to return to Washington.

4. President Kennedy’s aides drafted a speech announcing a military invasion of Cuba.

In a dramatic primetime address on October 22, 1962, Kennedy informed the nation of the naval blockade around Cuba. An alternative speech with a much different message had been drafted days before, however, in the event the president opted for a military strike. “This morning, I reluctantly ordered the armed forces to attack and destroy the nuclear buildup in Cuba,” began the address that JFK never delivered.

5. A Soviet spy was a valuable mole.

Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, a Soviet military intelligence officer, passed along vital espionage about Soviet missile systems—including technical manuals—to the CIA and British intelligence officials. That knowledge proved extremely valuable for the CIA agents analyzing the aerial photographs taken over Cuba. On October 22, 1962, KGB officials arrested Penkovsky in Moscow, and it is believed he was convicted of espionage and executed in 1963.

President Kennedy addresses the nation about the Cuban Missile Crisis on October 22, 1962. (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

6. There were American combat fatalities.

On October 27, 1962, a Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missile downed an American U-2 plane, killing its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson Jr. President Kennedy posthumously awarded him the Distinguished Service Medal. Four days before Anderson’s death, a C-135 Air Force transport bringing supplies to Guantanamo Naval Air Station on Cuba crashed on landing, killing its crew of seven.

7. Both sides compromised.

U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk said of the Cuban Missile Crisis, “We’re eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked.” That assessment is too one-sided. While on October 28, 1962, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev ordered the removal of Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba, it wasn’t a unilateral move. The Americans also secretly pledged to withdraw intermediate nuclear missiles from Turkey and not to invade Cuba.

8. Secret back-door diplomacy, rather than brinkmanship, defused the crisis.

Once Kennedy announced the blockade, the Americans and Soviets were in regular communication. The October 28 agreement was hammered out the night before in a secret meeting between Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. The Attorney General’s outreach and offer to remove missiles from Turkey was so clandestine that only a handful of presidential advisers were aware of it at the time.

Members of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council leave the White House on October 29, 1962. (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

9. The Cuban Missile Crisis lasted more than just 13 days.

Yes, it was 13 days from when Bundy showed Kennedy the incriminating U-2 photographs to Radio Moscow’s announcement of Khrushchev’s decision to remove the missiles, and the number has been drilled into history with Robert Kennedy’s posthumous memoir “Thirteen Days” and the 2000 motion picture of the same name. But even though the world breathed a sigh of relief after the news of that 13th day, the tense situation did not suddenly abate. The U.S. military remained on its highest state of alert for three more weeks as it monitored the removal of the missiles.

10. Although the Kennedy administration thought all the Soviet nukes were gone, they weren’t.

President Kennedy, satisfied with Soviet assurances that all nuclear weapons had been removed, lifted the Cuban blockade on November 20, 1962. Recently unearthed Soviet documents have revealed, however, that while Khrushchev dismantled the medium- and intermediate-range missiles known to the Kennedy administration, he left approximately 100 tactical nuclear weapons—of which the Americans were unaware for decades—for possible use in repelling invading forces. Khrushchev had intended to train the Cubans and transfer the missiles to them, as long as they kept their presence a secret. Soviet concerns about whether Castro could be trusted with the weapons mounted, however, and they finally removed the last of the nuclear warheads from Cuba on December 1, 1962.