Jupiter: Our Solar System’s Largest Planet

Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system. Fittingly, it was named after the king of the gods in Roman mythology. In a similar manner, the ancient Greeks named the planet after Zeus, the king of the Greek pantheon.

Jupiter helped revolutionize the way we saw the universe and ourselves in 1610, when Galileo discovered Jupiter’s four large moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, now known as the Galilean moons. This was the first time that celestial bodies were seen circling an object other than Earth, and gave major support to the Copernican view that Earth was not the center of the universe.

NASA: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/jupiter/overview/

Physical characteristics

Jupiter is more than twice as massive as all the other planets combined. If the enormous planet was about 80 times more massive, it would have actually become a star instead of a planet. Jupiter’s immense volume could hold more than 1,300 Earths. That means that if Jupiter were the size of a basketball, Earth would be the size of a grape.

Jupiter has a dense core of uncertain composition, surrounded by a helium-rich layer of fluid metallic hydrogen that extends out to 80% to 90% of the diameter of the planet.

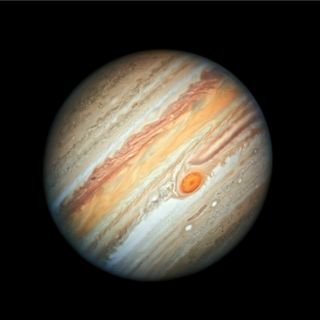

Jupiter’s atmosphere resembles that of the sun, made up mostly of hydrogen and helium. The colorful light and dark bands that surround Jupiter are created by strong east-west winds in the planet’s upper atmosphere traveling more than 335 mph (539 km/h). The white clouds in the light zones are made of crystals of frozen ammonia, while darker clouds made of other chemicals are found in the dark belts. At the deepest visible levels are blue clouds. Far from being static, the stripes of clouds change over time. Inside the atmosphere, diamond rain may fill the skies.

The most extraordinary feature on Jupiter is the Great Red Spot, a giant hurricane-like storm that’s lasted more than 300 years. At its widest, the Great Red Spot is about twice the size of Earth, and its edge spins counterclockwise around its center at speeds of about 270 to 425 mph (430 to 680 km/h). The color of the storm, which usually varies from brick red to slightly brown, may come from small amounts of sulfur and phosphorus in the ammonia crystals in Jupiter’s clouds. The spot has been shrinking for quite some time, although the rate may be slowing in recent years.

Jupiter’s gargantuan magnetic field is the strongest of all the planets in the solar system at nearly 20,000 times the strength of Earth’s. It traps electrically charged particles in an intense belt of electrons and other electrically charged particles that regularly blasts the planet’s moons and rings with radiation more than 1,000 times the lethal level for a human, enough to damage even heavily shielded spacecraft, such as NASA’s Galileo probe. The magnetosphere of Jupiter swells out some 600,000 to 2 million miles (1 million to 3 million kilometers) toward the sun and tapers to a tail extending more than 600 million miles (1 billion km) behind the massive planet.

Jupiter also spins faster than any other planet, taking a little under 10 hours to complete a turn on its axis, compared with 24 hours for Earth. This rapid spin makes Jupiter bulge at the equator and flatten at the poles.

Jupiter broadcasts radio waves strong enough to detect on Earth. These come in two forms — strong bursts that occur when Io, the closest of Jupiter’s large moons, passes through certain regions of Jupiter’s magnetic field, and continuous radiation from Jupiter’s surface and high-energy particles in its radiation belts.

Orbit & rotation

Average distance from the sun: 483,682,810 miles (778,412,020 km). By comparison: 5.203 times that of Earth.

Perihelion (closest approach to the sun): 460,276,100 miles (740,742,600 km). By comparison: 5.036 times that of Earth.

Aphelion (farthest distance from the sun): 507,089,500 miles (816,081,400 km). By comparison: 5.366 times that of Earth.

Jupiter’s moons

With four large moons and many smaller moons in orbit around it, Jupiter by itself forms a kind of miniature solar system.

Jupiter has 79 known moons, which are mostly named after the paramours of Roman gods. The four largest moons of Jupiter, called Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, were discovered by Galileo Galilei.

Ganymede is the largest moon in our solar system, and is larger than Mercury and Pluto. It is also the only moon known to have its own magnetic field. The moon has at least one ocean between layers of ice, although it may contain several layers of both ice and water, stacked on top of one another. Ganymede will be the main target of the European Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft that’s scheduled to launch in 2022 and arrive at Jupiter’s system in 2030.

Io is the most volcanically active body in our solar system. The sulfur its volcanoes spew gives Io a blotted yellow-orange appearance that looks kind of like a pepperoni pizza. As Io orbits Jupiter, the planet’s immense gravity causes “tides” in Io’s solid surface that rise 300 feet (100 meters) high and generate enough heat for volcanic activity.

The frozen crust of Europa is made up mostly of water ice, and it may hide a liquid ocean that contains twice as much water as Earth does. Some of this liquid spouts from the surface in newly spotted sporadic plumes at Europa’s southern pole. NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, a planned spacecraft that would launch in the 2020s to explore the icy moon, is now in phase B (the design stage). It would perform 40 to 45 flybys to examine the habitability of the moon.

Callisto has the lowest reflectivity, or albedo, of the four Galilean moons. This suggests that its surface may be composed of dark, colorless rock.

Jupiter’s rings

Jupiter’s three rings came as a surprise when NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft discovered them around the planet’s equator in 1979. Each are much fainter than Saturn’s rings.

The main ring is flattened. It is about 20 miles (30 km) thick and more than 4,000 miles (6,400 km) wide.

The inner cloud-like ring, called the halo, is about 12,000 miles (20,000 km) thick. The halo is caused by electromagnetic forces that push grains away from the plane of the main ring. This structure extends halfway from the main ring down to the planet’s cloud tops and expands. Both the main ring and halo are composed of small, dark particles of dust.

The third ring, known as the gossamer ring because of its transparency, is actually three rings of microscopic debris from three of Jupiter’s moons, Amalthea, Thebe and Adrastea. It is probably made up of dust particles less than 10 microns in diameter, about the same size of the particles found in cigarette smoke, and extends to an outer edge of about 80,000 miles (129,000 km) from the center of the planet and inward to about 18,600 miles (30,000 km).

Ripples in the rings of both Jupiter and Saturn may be signs of impacts from comets and asteroids.

Research & exploration

Seven missions have flown by Jupiter — Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, Voyager 2, Ulysses, Cassini and New Horizons. Two missions — NASA’s Galileo and Juno missions — have orbited the planet. Two future missions are planned to study Jupiter’s moons: NASA’s Europa Clipper (which would launch in the 2020s) and the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) that will launch in 2022 and arrive at Jupiter’s system in 2030 to study Ganymede, Callisto and Europa.

Pioneer 10 revealed how dangerous Jupiter’s radiation belt is, while Pioneer 11 provided data on the Great Red Spot and close-up pictures of Jupiter’s polar regions. Voyager 1 and 2 helped astronomers create the first detailed maps of the Galilean satellites, discovered Jupiter’s rings, revealed sulfur volcanoes on Io and detected lightning in Jupiter’s clouds. Ulysses discovered the solar wind has a much greater impact on Jupiter’s magnetosphere than what was previously suggested. New Horizons took close-up pictures of Jupiter and its largest moons.

In 1995, Galileo sent a probe plunging toward Jupiter, making the first direct measurements of the planet’s atmosphere and measuring the amount of water and other chemicals there. When Galileo ran low on fuel, the craft was intentionally crashed into Jupiter to avoid any risk of it slamming into and contaminating Europa, which might have an ocean below its surface capable of supporting life.

Juno is the only mission at Jupiter at the moment. Juno studies Jupiter from a polar orbit to figure out how it and the rest of the solar system formed, which could shed light on how alien planetary systems might have developed. One of its key findings so far was discovering that Jupiter’s core may be larger than what scientists expected.

As the most massive body in the solar system after the sun, the pull of Jupiter’s gravity has helped shape the fate of our system. Jupiter’s gravity is likely responsible for violently hurling Neptune and Uranus outward. Jupiter, along with Saturn, may have slung a barrage of debris toward the inner planets early in the system’s history, although some scientists debate how much of a role each planet played in moving the asteroids around. Jupiter may also help keep asteroids from bombarding Earth, and recent events have shown that Jupiter can absorb some pretty significant impacts. Observations by amateurs have shown that Jupiter receives a few major impacts per decade, far more than what was predicted when Comet Shoemaker Levy-9 crashed into the planet in 1994.

Currently, Jupiter’s gravitational field influences numerous asteroids that have clustered into the regions preceding and following Jupiter in its orbit around the sun. These are known as the Trojan asteroids, after three large asteroids there, Agamemnon, Achilles and Hector. Their names were drawn from the Iliad, Homer’s epic about the Trojan War.

Could there be life on Jupiter?

Jupiter’s atmosphere grows warmer with depth, reaching room temperature, or 70 degrees F (21 degrees C), at an altitude where the atmospheric pressure is about 10 times as great as it is on Earth. Scientists suspect that if Jupiter has any form of life, it might dwell at this level, and it would have to be airborne. However, researchers have found no evidence for life on Jupiter.

10 Need-to-Know Things About Jupiter

THE GRANDEST PLANET

Eleven Earths could fit across Jupiter’s equator. If Earth were the size of a grape, Jupiter would be the size of a basketball.

FIFTH PLANET FROM OUR STAR

Jupiter orbits about 484 million miles (778 million kilometers) or 5.2 Astronomical Units (AU) from our Sun (Earth is one AU from the Sun).

SHORT DAY/LONG YEAR

Jupiter rotates once about every 10 hours (a Jovian day), but takes about 12 Earth years to complete one orbit of the Sun (a Jovian year).

JUPITER AND IO

WHAT’S INSIDE

Jupiter is a gas giant and so lacks an Earth-like surface. If it has a solid inner core at all, it’s likely only about the size of Earth.

MASSIVE WORLD, LIGHT ELEMENTS

Jupiter’s atmosphere is made up mostly of hydrogen (H2) and helium (He).

WORLDS GALORE

Jupiter has more than 75 moons.

RINGED WORLD

In 1979 the Voyager mission discovered Jupiter’s faint ring system. All four giant planets in our solar system have ring systems.

EXPLORING JUPITER

Nine spacecraft have visited Jupiter. Seven flew by and two have orbited the gas giant. Juno, the most recent, arrived at Jupiter in 2016.

INGREDIENTS FOR LIFE?

Jupiter cannot support life as we know it. But some of Jupiter’s moons have oceans beneath their crusts that might support life.

SUPER STORM

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a gigantic storm that’s about twice the size of Earth and has raged for over a century.