The 2008 Crash: What Happened to All That Money?

A trader works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on September 15, 2008 in New York City. In afternoon trading the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell over 500 points as U.S. stocks suffered a steep loss after news of the financial firm Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The warning signs of an epic financial crisis were blinking steadily through 2008—for those who were paying close attention.

One clue? According to the ProQuest newspaper database, the phrase “since the Great Depression” appeared in The New York Times nearly twice as often in the first eight months of that year—about two dozen times—as it did in an entire ordinary year. As the summer stretched into September, these nervous references began to noticeably accumulate, speckling the broadsheet columns like a first, warning sprinkle of ash before the ruinous arrival of wildfire.

In mid-September catastrophe erupted, dramatically and in full public view. Financial news became front-page, top-of-the-hour news, as hundreds of dazed-looking Lehman Brothers employees poured onto the sidewalks of Seventh Avenue in Manhattan, clutching office furnishings while struggling to explain to the swarming reporters the shocking turn of events. Why had their venerable 158-year-old investment banking firm, a bulwark of Wall Street, gone bankrupt? And what did it mean for most of the planet?

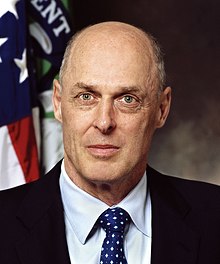

The superficially composed assessments that emanated from Washington policymakers added no clarity. The secretary of the treasury, Hank Paulson, had—reporters said—”concluded that the financial system could survive the collapse of Lehman.” In other words, the U.S. government decided not to engineer the firm’s salvation, as it had for Lehman’s competitor Merrill Lynch, the insurance giant American International Group (AIG) or, in the spring of 2008, the investment bank Bear Stearns.

Then-President George W. Bush had no explanations. He could only urge fortitude. “In the short run, adjustments in the financial markets can be painful—both for the people concerned about their investments and for the employees of the affected firms,” he said, attempting to quell potential panic on Main Street. “In the long run, I’m confident that our capital markets are flexible and resilient and can deal with these adjustments.” Privately, he sounded less sure, saying to advisors, “Someday you guys are going to need to tell me how we ended up with a system like this.… We’re not doing something right if we’re stuck with these miserable choices.”

Then-President George W. Bush had no explanations. He could only urge fortitude. “In the short run, adjustments in the financial markets can be painful—both for the people concerned about their investments and for the employees of the affected firms,” he said, attempting to quell potential panic on Main Street. “In the long run, I’m confident that our capital markets are flexible and resilient and can deal with these adjustments.” Privately, he sounded less sure, saying to advisors, “Someday you guys are going to need to tell me how we ended up with a system like this.… We’re not doing something right if we’re stuck with these miserable choices.”

And because that system had become a globally interdependent one, the U.S. financial crisis precipitated a worldwide economic collapse. So…what happened?

The American Dream was sold on too-easy credit

The 2008 financial crisis had its origins in the housing market, for generations the symbolic cornerstone of American prosperity. Federal policy conspicuously supported the American dream of homeownership since at least the 1930s, when the U.S. government began to back the mortgage market. It went further after WWII, offering veterans cheap home loans through the G.I. Bill. Policymakers reasoned they could avoid a return to prewar slump conditions so long as the undeveloped lands around cities could fill up with new houses, and the new houses with new appliances, and the new driveways with new cars. All this new buying meant new jobs, and security for generations to come.

The salesmen could make these deals without investigating a borrower’s fitness or a property’s value because the lenders they represented had no intention of keeping the loans. Lenders would sell these mortgages onward; bankers would bundle them into securities and peddle them to institutional investors eager for the returns the American housing market had yielded so consistently since the 1930s. The ultimate mortgage owners would often be thousands of miles away and unaware of what they had bought. They knew only that the rating agencies said it was as safe as houses always had been, at least since the Depression.

The fresh 21-century interest in transforming mortgages into securities owed to several factors. After the Federal Reserve System imposed low interest rates to avert a recession after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, ordinary investments weren’t yielding much. So savers sought superior yields.

To meet this demand for higher returns, the U.S. financial sector developed securities backed by mortgage payments. Ratings agencies, like Moody’s or Standard and Poor’s, gave high marks to the processed mortgage products, grading them AAA, or as good as U.S. Treasury bonds. And financiers regarded them as reliable, pointing to data and trends dating back decades. Americans almost always made their mortgage payments. The only problem with relying on those data and trends was that American laws and regulations had recently changed. The financial environment of the early 21st century looked more like the United States before the Depression than after: a country on the brink of a crash.

An employee of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. carrying a box out of the company’s headquarters after it filed for bankruptcy.

Chris Hondros/Getty Images

Post-Depression bank regulations were slowly chipped away

To prevent the Great Depression from ever happening again, the U.S. government subjected banks to stringent regulation. Franklin Roosevelt had campaigned on this issue as part of his New Deal in 1932, telling voters his administration would closely regulate securities trading: “Investment banking is a legitimate concern. Commercial banking is another wholly separate and distinct business. Their consolidation and mingling is contrary to public policy. I propose their separation.”

To prevent the Great Depression from ever happening again, the U.S. government subjected banks to stringent regulation. Franklin Roosevelt had campaigned on this issue as part of his New Deal in 1932, telling voters his administration would closely regulate securities trading: “Investment banking is a legitimate concern. Commercial banking is another wholly separate and distinct business. Their consolidation and mingling is contrary to public policy. I propose their separation.”

He and his party kept this promise. First, they insured commercial banks and the savers they served through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Then, with the Banking Act of 1933 (a.k.a. the Glass-Steagall Act), they separated these newly secure institutions from the investment banks that engaged in riskier financial endeavors. For decades afterward, such restrictive regulation ensured, as the adage went, that bankers had only to follow rule 363: pay depositors 3 percent, charge borrowers 6 percent, and hit the golf course by 3 p.m.

** In 1933, in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash and during a nationwide commercial bank failure and the Great Depression, two members of Congress put their names on what is known today as the Glass–Steagall Act (GSA). This act separated investment and commercial banking activities.**

Investment banks jumped neck-deep into risk

These nimbler firms, crowded by bigger brethren out of deals they might once have made, now had to seek riskier and more complicated ways to make money. Congress gave them one way to do so in 2000, with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, deregulating over-the-counter derivatives—securities that were essentially bets that two parties could privately make on the future price of an asset.

These nimbler firms, crowded by bigger brethren out of deals they might once have made, now had to seek riskier and more complicated ways to make money. Congress gave them one way to do so in 2000, with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, deregulating over-the-counter derivatives—securities that were essentially bets that two parties could privately make on the future price of an asset.

Like, for example, bundled mortgages.

stage was now set for investment banks to reap immense near-term profits by betting on the continuing rise of real-estate values—and also for such banks to fail once the billions on their balanced sheets proved illusory because ultimately, overextended American borrowers— who had been sold more debt than they could afford, secured on ephemeral assets—began to default. In an ever-speeding spiral, the bundled mortgage securities lost their AAA credit ratings, and banks fell headlong into bankruptcy.

Former employees of financial giant Lehman Brothers leaving the New York City headquarters.

(Susan Watts/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

The Bush administration, criticized for earlier bailouts, cut Lehman loose

In March 2008, the investment bank Bear Stearns began to go under, so the U.S. treasury and the Federal Reserve system brokered, and partly financed, a deal for its acquisition by JPMorgan Chase. In September, the treasury announced it would rescue the government-supervised mortgage underwriters almost universally known as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

In March 2008, the investment bank Bear Stearns began to go under, so the U.S. treasury and the Federal Reserve system brokered, and partly financed, a deal for its acquisition by JPMorgan Chase. In September, the treasury announced it would rescue the government-supervised mortgage underwriters almost universally known as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

President George W. Bush was a conservative Republican who, along with most of his appointees, believed in the virtue of deregulation. But with a crisis upon them, Bush and his lieutenants, particularly Treasury Secretary Pauls

President George W. Bush was a conservative Republican who, along with most of his appointees, believed in the virtue of deregulation. But with a crisis upon them, Bush and his lieutenants, particularly Treasury Secretary Pauls on and Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, decided not to bet on leaving the markets unfettered. Although not required by law to bail out Bear, Fannie or Freddie, they did so to avoid disaster—only to be castigated by fellow Republican believers in deregulation. Senator Jim Bunning of Kentucky called the bailouts “a calamity for our free-market system” and, essentially, “socialism”—albeit the sort of socialism that favored Wall Street, rather than workers.

on and Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, decided not to bet on leaving the markets unfettered. Although not required by law to bail out Bear, Fannie or Freddie, they did so to avoid disaster—only to be castigated by fellow Republican believers in deregulation. Senator Jim Bunning of Kentucky called the bailouts “a calamity for our free-market system” and, essentially, “socialism”—albeit the sort of socialism that favored Wall Street, rather than workers.

Earlier in the year, Paulson had identified Lehman as a potential problem and spoke privately to its chief executive, Richard Fuld. Months passed as Fuld failed to find a buyer for his firm. Exasperated with Fuld and stung by criticism from his fellow Republicans, Paulson told Treasury staff to comment—anonymously but on the record—that the government would not rescue Lehman.

By the weekend of September 13-14, 2008, Lehman was clearly finished, with perhaps tens of billions of dollars in overvalued assets on its balance sheets. Anyone who still held Lehman securities on the assumption that the government would bail them out had bet wrong.

A series of bankruptcies and mergers followed as skittish investors, seeking safe harbor, pulled their money out of supposedly high-return vehicles. Their preferred shelter: the U.S. treasury, into whose bonds and bills the terrified financiers of the world poured what liquid wealth they had left. After decades of trying to push the U.S. government out of banking, it turned out that in the end, the U.S. government was the only institution the bankers trusted. Starved of capital and credit, the economy faltered, and a long slump began.

Eric Rauchway is the author of several books on US history including Winter War and The Money Makers. He teaches at the University of California, Davis, and you can find him on Twitter @rauchway.

History Reads is a weekly series featuring work from Team History, a group of experts and influencers, exploring history’s most fascinating questions.