The Middle Ages, or Medieval Times, in Europe was a long period of history from 500 AD to 1500 AD. That’s 1000 years! It covers the time from the fall of the Roman Empire to the rise of the Ottoman Empire.

This was a time of castles and peasants, guilds and monasteries, cathedrals and crusades. Great leaders such as Joan of Arc and Charlemagne were part of the Middle Ages as well as major events such as the Black Plague and the rise of Islam.

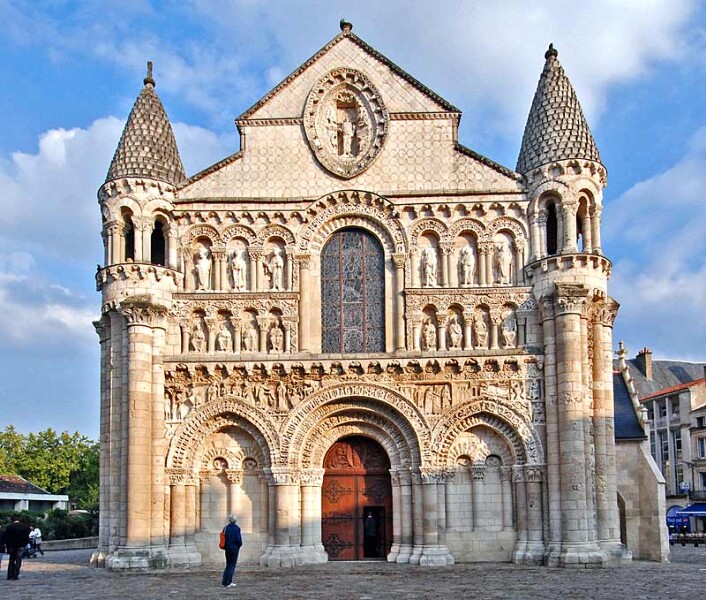

Notre Dame by Adrian Pingstone

Middle Ages, Medieval Times, Dark Ages: What’s the Difference?

When people use the terms Medieval Times, Middle Ages, and Dark Ages they are generally referring to the same period of time. The Dark Ages is usually referring to the first half of the Middle Ages from 500 to 1000 AD.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, a lot of the Roman culture and knowledge was lost. This included art, technology, engineering, and history. Historians know a lot about Europe during the Roman Empire because the Romans kept excellent records of all that happened. However, the time after the Romans is “dark” to historians because there was no central government recording events. This is why historians call this time the Dark Ages.

Although the term Middle Ages covers the years between 500 and 1500 throughout the world, this timeline is based on events specifically in Europe during that time. Go here to learn about the Islamic Empire during the Middle Ages.

Heidelberg Castle by Goutamkhandelwal

Timeline

- 476 – The fall of the Roman Empire. Rome had ruled much of Europe. Now much of the land would fall into confusion as local kings and rulers tried to grab power. This is the start of the Dark Ages or the Middle Ages.

- 481 – Clovis becomes King of the Franks. Clovis united most of the Frankish tribes that were part of Roman Province of Gaul.

- 570 – Muhammad, prophet of Islam is born.

- 732 – Battle of Tours. The Franks defeat the Muslims turning back Islam from Europe.

- 800 – Charlemagne, King of the Franks, is crowned Holy Roman Emperor. Charlemagne united much of Western Europe and is considered the father of both the French and the German Monarchies.

- 835 – Vikings from the Scandinavian lands (Denmark, Norway, and Sweden) begin to invade northern Europe. They would continue until 1042.

- 896 – Alfred the Great, King of England, turns back the Viking invaders.

- 1066 – William of Normandy, a French Duke, conquers England in the Battle of Hastings. He became King of England and changed the country forever.

- 1096 – Start of the First Crusade. The Crusades were wars between the Holy Roman Empire and the Muslims over the Holy Land. There would be several Crusades over the next 200 years.

- 1189 – Richard I, Richard the Lionheart, becomes King of England.

- 1206 – The Mongol Empire is founded by Genghis Khan.

- 1215 – King John of England signs the Magna Carta. This document gave the people some rights and said the king was not above the law.

- 1271 – Marco Polo leaves on his famous journey to explore Asia.

- 1337 – The Hundred Years War begins between England and France for control of the French throne.

- 1347 – The Black Death begins in Europe. This horrible disease would kill around half of the people in Europe.

- 1431 – French heroine Joan of Arc is executed by England at the age of 19.

- 1444 – German inventor Johannes Gutenberg invents the printing press. This will signal the start of the Renaissance.

- 1453 – The Ottoman Empire captures the city of Constantinople. This signals the end of the Eastern Roman Empire also known as Byzantium.

- 1482 – Leonardo Da Vinci paints “The Last Supper.”

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or Medieval Period lasted from the 5th to the 15th century. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and merged into the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery.

People use the phrase “Middle Ages” to describe Europe between the fall of Rome in 476 CE and the beginning of the Renaissance in the 14th century. Many scholars call the era the “medieval period” instead; “Middle Ages,” they say, incorrectly implies that the period is an insignificant blip sandwiched between two much more important epochs.

THE MIDDLE AGES: BIRTH OF AN IDEA

The phrase “Middle Ages” tells us more about the Renaissance that followed it than it does about the era itself. Starting around the 14th century, European thinkers, writers and artists began to look back and celebrate the art and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. Accordingly, they dismissed the period after the fall of Rome as a “Middle” or even “Dark” age in which no scientific accomplishments had been made, no great art produced, no great leaders born. The people of the Middle Ages had squandered the advancements of their predecessors, this argument went, and mired themselves instead in what 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon called “barbarism and religion.”

This way of thinking about the era in the “middle” of the fall of Rome and the rise of the Renaissance prevailed until relatively recently. However, today’s scholars note that the era was as complex and vibrant as any other.

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

After the fall of Rome, no single state or government united the people who lived on the European continent. Instead, the Catholic Church became the most powerful institution of the medieval period. Kings, queens and other leaders derived much of their power from their alliances with and protection of the Church.

(In 800 CE, for example, Pope Leo III named the Frankish king Charlemagne the “Emperor of the Romans”–the first since that empire’s fall more than 300 years before. Over time, Charlemagne’s realm became the Holy Roman Empire, one of several political entities in Europe whose interests tended to align with those of the Church.)

Ordinary people across Europe had to “tithe” 10 percent of their earnings each year to the Church; at the same time, the Church was mostly exempt from taxation. These policies helped it to amass a great deal of money and power.

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE RISE OF ISLAM

Meanwhile, the Islamic world was growing larger and more powerful. After the prophet Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, Muslim armies conquered large parts of the Middle East, uniting them under the rule of a single caliph. At its height, the medieval Islamic world was more than three times bigger than all of Christendom.

Under the caliphs, great cities such as Cairo, Baghdad and Damascus fostered a vibrant intellectual and cultural life. Poets, scientists and philosophers wrote thousands of books (on paper, a Chinese invention that had made its way into the Islamic world by the 8th century). Scholars translated Greek, Iranian and Indian texts into Arabic. Inventors devised technologies like the pinhole camera, soap, windmills, surgical instruments, an early flying machine and the system of numerals that we use today. And religious scholars and mystics translated, interpreted and taught the Quran and other scriptural texts to people across the Middle East.

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES

Toward the end of the 11th century, the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land. Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.)

The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century. No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life.

THE MIDDLE AGES: ART AND ARCHITECTURE

Another way to show devotion to the Church was to build grand cathedrals and other ecclesiastical structures such as monasteries. Cathedrals were the largest buildings in medieval Europe, and they could be found at the center of towns and cities across the continent.

Between the 10th and 13th centuries, most European cathedrals were built in the Romanesque style. Romanesque cathedrals are solid and substantial: They have rounded masonry arches and barrel vaults supporting the roof, thick stone walls and few windows. (Examples of Romanesque architecture include the Porto Cathedral in Portugal and the Speyer Cathedral in present-day Germany.)

Around 1200, church builders began to embrace a new architectural style, known as the Gothic. Gothic structures, such as the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis in France and the rebuilt Canterbury Cathedral in England, have huge stained-glass windows, pointed vaults and arches (a technology developed in the Islamic world), and spires and flying buttresses. In contrast to heavy Romanesque buildings, Gothic architecture seems to be almost weightless. Medieval religious art took other forms as well. Frescoes and mosaics decorated church interiors, and artists painted devotional images of the Virgin Mary, Jesus and the saints.

Also, before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, even books were works of art. Craftsmen in monasteries (and later in universities) created illuminated manuscripts: handmade sacred and secular books with colored illustrations, gold and silver lettering and other adornments. In the 12th century, urban booksellers began to market smaller illuminated manuscripts, like books of hours, psalters and other prayer books, to wealthy individuals.

THE MIDDLE AGES: ECONOMICS AND SOCIETY

In medieval Europe, rural life was governed by a system scholars call “feudalism.” In a feudal society, the king granted large pieces of land called fiefs to noblemen and bishops. Landless peasants known as serfs did most of the work on the fiefs: They planted and harvested crops and gave most of the produce to the landowner. In exchange for their labor, they were allowed to live on the land. They were also promised protection in case of enemy invasion.

During the 11th century, however, feudal life began to change. Agricultural innovations such as the heavy plow and three-field crop rotation made farming more efficient and productive, so fewer farm workers were needed–but thanks to the expanded and improved food supply, the population grew. As a result, more and more people were drawn to towns and cities. Meanwhile, the Crusades had expanded trade routes to the East and given Europeans a taste for imported goods such as wine, olive oil and luxurious textiles. As the commercial economy developed, port cities in particular thrived. By 1300, there were some 15 cities in Europe with a population of more than 50,000.

In these cities, a new era was born: the Renaissance. The Renaissance was a time of great intellectual and economic change, but it was not a complete “rebirth”: It had its roots in the world of the Middle Ages.

Recommended books and references:

The Middle Ages by Fiona Macdonald. 1993.

Medieval Life: Eyewitness Books by Andrew Langley. 2004.

History of the World: The Early Middle Ages. 1990.

The Middle Ages : an illustrated history by Barbara A. Hanawalt. 1998.