Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of genocide in landmark ruling

On the morning of March 16, 1968, U.S. Army soldiers entered a Vietnamese hamlet named My Lai 4 on a search-and-destroy mission in a region controlled by Viet Cong forces that the Army referred to as “Pinkville.” The soldiers didn’t encounter any enemy troops. Yet they proceeded to set huts on fire, gang-rape the women, and murder some 500 unarmed civilians including approximately 50 children under the age of four.

On the 50th anniversary of the My Lai massacre, the barbaric act still remains difficult to fathom. The massacre stands among the most infamous of wartime atrocities committed by any U.S. military force.

When news of the massacre finally hit newsstands more than a year and a half after it had occurred, it swiftly became emblematic of the U.S. war effort in Vietnam. Especially in the eyes of the war’s critics, the massacre was proof that America’s moral compass no longer functioned, as well as evidence that the government’s claim of “defending” Southeast Asia from atheistic communist aggression had become a cruel and paradoxical hoax.

The military’s secrecy ultimately compounded the shock of the revelations once they became public. Not only had scores of Army soldiers participated in the wanton murder of defenseless women and children, but the Army’s leadership had seemed to conspire to sweep crimes against humanity under the carpet.

The Tet Offensive that preceded the massacre at My Lai by less than two months led to graphic televised scenes and photographs that gripped the American public day after day. In contrast to the instantaneity of Tet’s news coverage, My Lai triggered a cover up by the Army that served to keep the massacre secret from the American public for a staggering 20 months during an election year. The U.S. military had deceived the public about the course of the war for years, but this was a concerted effort to hide an act of barbarism and turn it into a resounding victory over the Viet Cong.

Vietnamese children about to be shot by US Army soldiers during pursuit of Vietcong militia, as per order of Lieutenant Calley Jr. (later court-martialed), an incident which became known as the My Lai Massacre, on March 16, 1968 in My Lai, South Vietnam. (Credit: Ronald S. Haeberle/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

The atrocity itself was a deeply inhumane act. American soldiers stabbed, clubbed, and carved “C [for Charlie] Company” into the chests of their victims; and herded them into ditches and blew them to bits with grenades. One soldier recalled cutting victims’ throats and chopping off their hands. “A lot of people were doing it and I just followed,” he said. “I lost all sense of direction.”

In his gripping account My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness, Howard Jones reveals that this collective act of barbarism was far from an aberration by a small group of frightened and confused men, but a predictable result due to the way the war was being waged. The Army had dehumanized the Vietnamese people as “Gooks” and depicted women and children as potentially lethal combatants, while jungle warfare had fostered “an environment in which [U.S. troops] could not be sure who or where the enemy was,” Jones writes.

Members of Charlie Company, which committed the bulk of the atrocities, had seen comrades killed by land mines and sniper fire, even heard one being skinned alive, and in the words of one troop, they had become “leaderless, directionless, armed to the teeth, and making up their own rules…” Their confusion was only bolstered by official military policy. At the time, the combat strategies and tactics in use—including an emphasis on “search-and-destroy” missions and “free-fire zones”—encouraged troops to destroy entire hamlets and villages and defoliate forests. This, in turn, inflated enemy kill rates (the Pentagon’s measure of the war’s progress).

Hugh C. Thompson Army helicopter pilot, meeting with newsmen after appearing before an Army hearing at the Pentagon into the original investigation of the massacre at My Lai, 1969. (Credit: AP Photo)

Although the public would not find out what happened for nearly two years, word of the atrocity quickly spread among troops in Vietnam. Some American GIs refused to remain silent about the Army’s cover up of the grisly deaths of unarmed women and children at the hands of U.S. soldiers. Helicopter pilot Hugh Thompson, for example, had tried to stop some of the soldiers from massacring civilians during the assault, and he and two others informed commanders about the war crime within hours, to little avail.

Helicopter door gunner, Ronald Ridenhour, who had been told of the My Lai killings by soldiers who had taken part in the slaughter, returned to his home in Phoenix and compiled a dossier of facts about it. On March 18, 1969, almost one year to the day of the massacre, Ridenhour sent a letter to 30 Washington officials detailing the My Lai massacre. Two investigations—one focused on establishing whether a massacre had occurred; the other into a potential cover up by Army brass—were launched.

Soon, freelance reporter Seymour Hersh got a tip that Charlie Company’s Lt. William Calley was being court-martialed on charges that he had killed Vietnamese civilians. Hersh interviewed Calley about his role in the slaughter, but Calley insisted that My Lai had been a fierce firefight with the Viet Cong, not an assault on unarmed villagers. Hersh talked to others who were there, however, and in November 1969 he reported that an unparalleled atrocity had taken place in My Lai in a graphic story that appeared in dozens of newspapers.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer soon published Army photographer Ronald Haeberle’s private photos documenting the slaughter. These first news accounts pricked the nation’s conscience and set off a debate about what had actually happened, what the event said about America’s war effort, and who bore responsibility for the massacre.

More than a dozen military servicemen were eventually charged with crimes, but Calley was the only one who was convicted. In spite of growing opposition to the war, much of the American public remained supportive of its soldiers, and was reluctant to pin the blame on them for simply following the orders of their commanders. This climate made it harder to charge senior military leaders, let alone win convictions in military courtrooms.

Pham Thi Trinh, one of the few survivors of My Lai Massacre, standing in front of monument honoring victims. (Credit: Dirck Halstead/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images)

My Lai didn’t occur in isolation, of course. The U.S. government for years had deceived the public about the war’s progress, and dogged investigative reporting including publication of the Pentagon Papers were beginning to reveal the level of official deception. After the Tet Offensive in early 1968, a majority of the American public came to view the war as a mistake, and the subsequent cover up of My Lai served to deepen people’s despair that the war could ever be won. The massacre also raised big questions about whether the United States was capable of defending freedom, democracy, and human rights in far-flung places.

Rather than liberating concentration camps and promoting universal notions of human dignity, the United States now seemed to some Americans to have been complicit in covering up war crimes. At the same time, Americans who still supported the war in 1969 thought that Calley was just carrying out orders and had become the fall guy for higher-ups looking to take the spotlight off their own Vietnam-era blunders. Finally, My Lai created an unflattering portrait of GIs, and led to the shoddy treatment some returning soldiers received when they rotated back home from Vietnam.

The My Lai massacre and the Army’s cover up are a particularly dark moment in the history of modern America. Had the Army taken reports of atrocities seriously from day one; had it launched an investigation and made the findings public, perhaps the country would have had more faith in its institutions. Although the system ruptured in horrific ways during the assault on My Lai, others might have seen it working by holding those responsible for the crimes accountable. That’s not the way the aftermath transpired, and as a result, the legacy of the massacre remains even more haunting than it might have been.

Matthew Dallek, associate professor at George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management, is author, most recently, of Defenseless Under the Night: The Roosevelt Years and the Origins of Homeland Security.

The Vietnam War was a long, costly and divisive conflict that pitted the communist government of North Vietnam against South Vietnam and its principal ally, the United States. The conflict was intensified by the ongoing Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. More than 3 million people (including over 58,000 Americans) were killed in the Vietnam War, and more than half of the dead were Vietnamese civilians. Opposition to the war in the United States bitterly divided Americans, even after President Richard Nixon ordered the withdrawal of U.S. forces in 1973. Communist forces ended the war by seizing control of South Vietnam in 1975, and the country was unified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam the following year.

Vietnam, a nation in Southeast Asia on the eastern edge of the Indochinese peninsula, had been under French colonial rule since the 19th century.

During World War II, Japanese forces invaded Vietnam. To fight off both Japanese occupiers and the French colonial administration, political leader Ho Chi Minh—inspired by Chinese and Soviet communism—formed the Viet Minh, or the League for the Independence of Vietnam.

During World War II, Japanese forces invaded Vietnam. To fight off both Japanese occupiers and the French colonial administration, political leader Ho Chi Minh—inspired by Chinese and Soviet communism—formed the Viet Minh, or the League for the Independence of Vietnam.

Following its 1945 defeat in World War II, Japan withdrew its forces from Vietnam, leaving the French-educated Emperor Bao Dai in control. Seeing an opportunity to seize control, Ho’s Viet Minh forces immediately rose up, taking over the northern city of Hanoi and declaring a Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) with Ho as president.

Seeking to regain control of the region, France backed Emperor Bao and set up the state of Vietnam in July 1949, with the city of Saigon as its capital.

Seeking to regain control of the region, France backed Emperor Bao and set up the state of Vietnam in July 1949, with the city of Saigon as its capital.

Both sides wanted the same thing: a unified Vietnam. But while Ho and his supporters wanted a nation modeled after other communist countries, Bao and many others wanted a Vietnam with close economic and cultural ties to the West.

Did You Know?

The Vietnam War and active U.S. involvement in the war began in 1954, though ongoing conflict in the region had stretched back several decades.

After Ho’s communist forces took power in the north, armed conflict between northern and southern armies continued until a decisive battle at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954 ended in victory for northern Viet Minh forces. The French loss at the battle ended almost a century of French colonial rule in Indochina.

The subsequent treaty signed in July 1954 at a Geneva conference split Vietnam along the latitude known as the 17th Parallel (17 degrees north latitude), with Ho in control in the North and Bao in the South. The treaty also called for nationwide elections for reunification to be held in 1956.

In 1955, however, the strongly anti-communist politician Ngo Dinh Diem pushed Emperor Bao aside to become president of the Government of the Republic of Vietnam (GVN), often referred to during that era as South Vietnam.

With the Cold War intensifying worldwide, the United States hardened its policies against any allies of the Soviet Union, and by 1955 President Dwight D. Eisenhower had pledged his firm support to Diem and South Vietnam.

With the Cold War intensifying worldwide, the United States hardened its policies against any allies of the Soviet Union, and by 1955 President Dwight D. Eisenhower had pledged his firm support to Diem and South Vietnam.

With training and equipment from American military and the CIA, Diem’s security forces cracked down on Viet Minh sympathizers in the south, whom he derisively called Viet Cong (or Vietnamese Communist), arresting some 100,000 people, many of whom were brutally tortured and executed.

By 1957, the Viet Cong and other opponents of Diem’s repressive regime began fighting back with attacks on government officials and other targets, and by 1959 they had begun engaging the South Vietnamese army in firefights.

In December 1960, Diem’s many opponents within South Vietnam—both communist and non-communist—formed the National Liberation Front (NLF) to organize resistance to the regime. Though the NLF claimed to be autonomous and that most of its members were not communists, many in Washington assumed it was a puppet of Hanoi.

A team sent by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 to report on conditions in South Vietnam advised a build-up of American military, economic and technical aid in order to help Diem confront the Viet Cong threat.

A team sent by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 to report on conditions in South Vietnam advised a build-up of American military, economic and technical aid in order to help Diem confront the Viet Cong threat.

Working under the “domino theory,” which held that if one Southeast Asian country fell to communism, many other countries would follow, Kennedy increased U.S. aid, though he stopped short of committing to a large-scale military intervention.

By 1962, the U.S. military presence in South Vietnam had reached some 9,000 troops, compared with fewer than 800 during the 1950s.

A coup by some of his own generals succeeded in toppling and killing Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, in November 1963, three weeks before Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas.

The ensuing political instability in South Vietnam persuaded Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to further increase U.S. military and economic support.

The ensuing political instability in South Vietnam persuaded Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to further increase U.S. military and economic support.

In August of 1964, after DRV torpedo boats attacked two U.S. destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin, Johnson ordered the retaliatory bombing of military targets in North Vietnam. Congress soon passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave Johnson broad war-making powers, and U.S. planes began regular bombing raids, codenamed Operation Rolling Thunder, the following year.

In March 1965, Johnson made the decision—with solid support from the American public—to send U.S. combat forces into battle in Vietnam. By June, 82,000 combat troops were stationed in Vietnam, and military leaders were calling for 175,000 more by the end of 1965 to shore up the struggling South Vietnamese army.

Despite the concerns of some of his advisers about this escalation, and about the entire war effort amid a growing anti-war movement, Johnson authorized the immediate dispatch of 100,000 troops at the end of July 1965 and another 100,000 in 1966. In addition to the United States, South Korea, Thailand, Australia and New Zealand also committed troops to fight in South Vietnam (albeit on a much smaller scale).

In contrast to the air attacks on North Vietnam, the U.S.-South Vietnamese war effort in the south was fought primarily on the ground, largely under the command of General William Westmoreland, in coordination with the government of General Nguyen Van Thieu in Saigon.

In contrast to the air attacks on North Vietnam, the U.S.-South Vietnamese war effort in the south was fought primarily on the ground, largely under the command of General William Westmoreland, in coordination with the government of General Nguyen Van Thieu in Saigon.

Westmoreland pursued a policy of attrition, aiming to kill as many enemy troops as possible rather than trying to secure territory. By 1966, large areas of South Vietnam had been designated as “free-fire zones,” from which all innocent civilians were supposed to have evacuated and only enemy remained. Heavy bombing by B-52 aircraft or shelling made these zones uninhabitable, as refugees poured into camps in designated safe areas near Saigon and other cities.

Even as the enemy body count (at times exaggerated by U.S. and South Vietnamese authorities) mounted steadily, DRV and Viet Cong troops refused to stop fighting, encouraged by the fact that they could easily reoccupy lost territory with manpower and supplies delivered via the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Cambodia and Laos. Additionally, supported by aid from China and the Soviet Union, North Vietnam strengthened its air defenses.

By November 1967, the number of American troops in Vietnam was approaching 500,000, and U.S. casualties had reached 15,058 killed and 109,527 wounded. As the war stretched on, some soldiers came to mistrust the government’s reasons for keeping them there, as well as Washington’s repeated claims that the war was being won.

The later years of the war saw increased physical and psychological deterioration among American soldiers—both volunteers and draftees—including drug use, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mutinies and attacks by soldiers against officers and noncommissioned officers.

Between July 1966 and December 1973, more than 503,000 U.S. military personnel deserted, and a robust anti-war movement among American forces spawned violent protests, killings and mass incarcerations of personnel stationed in Vietnam as well as within the United States.

Bombarded by horrific images of the war on their televisions, Americans on the home front turned against the war as well: In October 1967, some 35,000 demonstrators staged a massive Vietnam War protest outside the Pentagon. Opponents of the war argued that civilians, not enemy combatants, were the primary victims and that the United States was supporting a corrupt dictatorship in Saigon.

By the end of 1967, Hanoi’s communist leadership was growing impatient as well, and sought to strike a decisive blow aimed at forcing the better-supplied United States to give up hopes of success.

On January 31, 1968, some 70,000 DRV forces under General Vo Nguyen Giap launched the Tet Offensive (named for the lunar new year), a coordinated series of fierce attacks on more than 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam.

Taken by surprise, U.S. and South Vietnamese forces nonetheless managed to strike back quickly, and the communists were unable to hold any of the targets for more than a day or two.

Reports of the Tet Offensive stunned the U.S. public, however, especially after news broke that Westmoreland had requested an additional 200,000 troops, despite repeated assurances that victory in the Vietnam War was imminent. With his approval ratings dropping in an election year, Johnson called a halt to bombing in much of North Vietnam (though bombings continued in the south) and promised to dedicate the rest of his term to seeking peace rather than reelection.

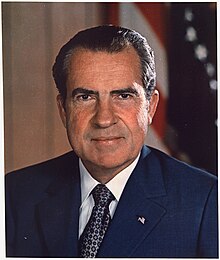

Johnson’s new tack, laid out in a March 1968 speech, met with a positive response from Hanoi, and peace talks between the U.S. and North Vietnam opened in Paris that May. Despite the later inclusion of the South Vietnamese and the NLF, the dialogue soon reached an impasse, and after a bitter 1968 election season marred by violence, Republican Richard M. Nixon won the presidency.

Johnson’s new tack, laid out in a March 1968 speech, met with a positive response from Hanoi, and peace talks between the U.S. and North Vietnam opened in Paris that May. Despite the later inclusion of the South Vietnamese and the NLF, the dialogue soon reached an impasse, and after a bitter 1968 election season marred by violence, Republican Richard M. Nixon won the presidency.

Nixon sought to deflate the anti-war movement by appealing to a “silent majority” of Americans who he believed supported the war effort. In an attempt to limit the volume of American casualties, he announced a program called Vietnamization: withdrawing U.S. troops, increasing aerial and artillery bombardment and giving the South Vietnamese the training and weapons needed to effectively control the ground war.

In addition to this Vietnamization policy, Nixon continued public peace talks in Paris, adding higher-level secret talks conducted by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger beginning in the spring of 1968.

In addition to this Vietnamization policy, Nixon continued public peace talks in Paris, adding higher-level secret talks conducted by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger beginning in the spring of 1968.

The North Vietnamese continued to insist on complete and unconditional U.S. withdrawal—plus the ouster of U.S.-backed General Nguyen Van Thieu—as conditions of peace, however, and as a result the peace talks stalled.

The next few years would bring even more carnage, including the horrifying revelation that U.S. soldiers had mercilessly slaughtered more than 400 unarmed civilians in the village of My Lai in March 1968.

After the My Lai Masscre, anti-war protests continued to build as the conflict wore on. In 1968 and 1969, there were hundreds of protest marches and gatherings throughout the country.

On November 15, 1969, the largest anti-war demonstration in American history took place in Washington, D.C., as over 250,000 Americans gathered peacefully, calling for withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam.

The anti-war movement, which was particularly strong on college campuses, divided Americans bitterly. For some young people, the war symbolized a form of unchecked authority they had come to resent. For other Americans, opposing the government was considered unpatriotic and treasonous.

As the first U.S. troops were withdrawn, those who remained became increasingly angry and frustrated, exacerbating problems with morale and leadership. Tens of thousands of soldiers received dishonorable discharges for desertion, and about 500,000 American men from 1965-73 became “draft dodgers,” with many fleeing to Canada to evade conscription. Nixon ended draft calls in 1972, and instituted an all-volunteer army the following year.

In 1970, a joint U.S-South Vietnamese operation invaded Cambodia, hoping to wipe out DRV supply bases there. The South Vietnamese then led their own invasion of Laos, which was pushed back by North Vietnam.

The invasion of these countries, in violation of international law, sparked a new wave of protests on college campuses across America. During one, on May 4, 1970, at Kent State University in Ohio, National Guardsmen shot and killed four students. At another protest 10 days later, two students at Jackson State University in Mississippi were killed by police.

By the end of June 1972, however, after a failed offensive into South Vietnam, Hanoi was finally willing to compromise. Kissinger and North Vietnamese representatives drafted a peace agreement by early fall, but leaders in Saigon rejected it, and in December Nixon authorized a number of bombing raids against targets in Hanoi and Haiphong. Known as the Christmas Bombings, the raids drew international condemnation.

In January 1973, the United States and North Vietnam concluded a final peace agreement, ending open hostilities between the two nations. War between North and South Vietnam continued, however, until April 30, 1975, when DRV forces captured Saigon, renaming it Ho Chi Minh City (Ho himself died in 1969).

More than two decades of violent conflict had inflicted a devastating toll on Vietnam’s population: After years of warfare, an estimated 2 million Vietnamese were killed, while 3 million were wounded and another 12 million became refugees. Warfare had demolished the country’s infrastructure and economy, and reconstruction proceeded slowly.

In 1976, Vietnam was unified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, though sporadic violence continued over the next 15 years, including conflicts with neighboring China and Cambodia. Under a broad free market policy put in place in 1986, the economy began to improve, boosted by oil export revenues and an influx of foreign capital. Trade and diplomatic relations between Vietnam and the U.S. resumed in the 1990s.

In the United States, the effects of the Vietnam War would linger long after the last troops returned home in 1973. The nation spent more than $120 billion on the conflict in Vietnam from 1965-73; this massive spending led to widespread inflation, exacerbated by a worldwide oil crisis in 1973 and skyrocketing fuel prices.

Psychologically, the effects ran even deeper. The war had pierced the myth of American invincibility and had bitterly divided the nation. Many returning veterans faced negative reactions from both opponents of the war (who viewed them as having killed innocent civilians) and its supporters (who saw them as having lost the war), along with physical damage including the effects of exposure to the toxic herbicide Agent Orange, millions of gallons of which had been dumped by U.S. planes on the dense forests of Vietnam.

In 1982, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was unveiled in Washington, D.C. On it were inscribed the names of 57,939 American men and women killed or missing in the war; later additions brought that total to 58,200.

On June 25, 1950, the Korean War began when some 75,000 soldiers from the North Korean People’s Army poured across the 38th parallel, the boundary between the Soviet-backed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to the north and the pro-Western Republic of Korea to the south. This invasion was the first military action of the Cold War.

By July, American troops had entered the war on South Korea’s behalf. As far as American officials were concerned, it was a war against the forces of international communism itself. After some early back-and-forth across the 38th parallel, the fighting stalled and casualties mounted with nothing to show for them. Meanwhile, American officials worked anxiously to fashion some sort of armistice with the North Koreans. The alternative, they feared, would be a wider war with Russia and China–or even, as some warned, World War III. Finally, in July 1953, the Korean War came to an end. In all, some 5 million soldiers and civilians lost their lives during the war. The Korean peninsula is still divided today.

“If the best minds in the world had set out to find us the worst possible location in the world to fight this damnable war,” U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson (1893-1971) once said, “the unanimous choice would have been Korea.” The peninsula had landed in America’s lap almost by accident. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Korea had been a part of the Japanese empire, and after World War II it fell to the Americans and the Soviets to decide what should be done with their enemy’s imperial possessions. In August 1945, two young aides at the State Department divided the Korean peninsula in half along the 38th parallel. The Russians occupied the area north of the line and the United States occupied the area to its south.

By the end of the decade, two new states had formed on the peninsula. In the south, the anti-communist dictator Syngman Rhee (1875-1965) enjoyed the reluctant support of the American government; in the north, the communist dictator Kim Il Sung (1912-1994) enjoyed the slightly more enthusiastic support of the Soviets. Neither dictator was content to remain on his side of the 38th parallel, however, and border skirmishes were common. Nearly 10,000 North and South Korean soldiers were killed in battle before the war even began.

Even so, the North Korean invasion came as an alarming surprise to American officials. As far as they were concerned, this was not simply a border dispute between two unstable dictatorships on the other side of the globe. Instead, many feared it was the first step in a communist campaign to take over the world. For this reason, nonintervention was not considered an option by many top decision makers. (In fact, in April 1950, a National Security Council report known as NSC-68 had recommended that the United States use military force to “contain” communist expansionism anywhere it seemed to be occurring, “regardless of the intrinsic strategic or economic value of the lands in question.”)

Even so, the North Korean invasion came as an alarming surprise to American officials. As far as they were concerned, this was not simply a border dispute between two unstable dictatorships on the other side of the globe. Instead, many feared it was the first step in a communist campaign to take over the world. For this reason, nonintervention was not considered an option by many top decision makers. (In fact, in April 1950, a National Security Council report known as NSC-68 had recommended that the United States use military force to “contain” communist expansionism anywhere it seemed to be occurring, “regardless of the intrinsic strategic or economic value of the lands in question.”)

“If we let Korea down,” President Harry Truman (1884-1972) said, “the Soviet[s] will keep right on going and swallow up one [place] after another.” The fight on the Korean peninsula was a symbol of the global struggle between east and west, good and evil. As the North Korean army pushed into Seoul, the South Korean capital, the United States readied its troops for a war against communism itself.

At first, the war was a defensive one–a war to get the communists out of South Korea–and it went badly for the Allies. The North Korean army was well-disciplined, well-trained and well-equipped; Rhee’s forces, by contrast, were frightened, confused, and seemed inclined to flee the battlefield at any provocation. Also, it was one of the hottest and driest summers on record, and desperately thirsty American soldiers were often forced to drink water from rice paddies that had been fertilized with human waste. As a result, dangerous intestinal diseases and other illnesses were a constant threat.

By the end of the summer, President Truman and General Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964), the commander in charge of the Asian theater, had decided on a new set of war aims. Now, for the Allies, the Korean War was an offensive one: It was a war to “liberate” the North from the communists.

Initially, this new strategy was a success. An amphibious assault at Inchon pushed the North Koreans out of Seoul and back to their side of the 38th parallel. But as American troops crossed the boundary and headed north toward the Yalu River, the border between North Korea and Communist China, the Chinese started to worry about protecting themselves from what they called “armed aggression against Chinese territory.” Chinese leader Mao Zedong (1893-1976) sent troops to North Korea and warned the United States to keep away from the Yalu boundary unless it wanted full-scale war.

This was something that President Truman and his advisers decidedly did not want: They were sure that such a war would lead to Soviet aggression in Europe, the deployment of atomic weapons and millions of senseless deaths. To General MacArthur, however, anything short of this wider war represented “appeasement,” an unacceptable knuckling under to the communists.

As President Truman looked for a way to prevent war with the Chinese, MacArthur did all he could to provoke it. Finally, in March 1951, he sent a letter to Joseph Martin, a House Republican leader who shared MacArthur’s support for declaring all-out war

As President Truman looked for a way to prevent war with the Chinese, MacArthur did all he could to provoke it. Finally, in March 1951, he sent a letter to Joseph Martin, a House Republican leader who shared MacArthur’s support for declaring all-out war  on China–and who could be counted upon to leak the letter to the press. “There is,” MacArthur wrote, “no substitute for victory” against international communism.

on China–and who could be counted upon to leak the letter to the press. “There is,” MacArthur wrote, “no substitute for victory” against international communism.

For Truman, this letter was the last straw. On April 11, the president fired the general for insubordination.

In July 1951, President Truman and his new military commanders started peace talks at Panmunjom. Still, the fighting continued along the 38th parallel as negotiations stalled. Both sides were willing to accept a ceasefire that maintained the 38th parallel boundary, but they could not agree on whether prisoners of war should be forcibly “repatriated.” (The Chinese and the North Koreans said yes; the United States said no.) Finally, after more than two years of negotiations, the adversaries signed an armistice on July 27, 1953. The agreement allowed the POWs to stay where they liked; drew a new boundary near the 38th parallel that gave South Korea an extra 1,500 square miles of territory; and created a 2-mile-wide “demilitarized zone” that still exists today.

The Korean War was relatively short but exceptionally bloody. Nearly 5 million people died. More than half of these–about 10 percent of Korea’s prewar population–were civilians. (This rate of civilian casualties was higher than World War II’s and Vietnam’s.) Almost 40,000 Americans died in action in Korea, and more than 100,000 were wounded.